Shamanism: An Invention of Anthropologists and New Age Teachers

The summer of 2018 began with Brad’s vision of a woman shaman who had glowing red antlers on top of her head. Another character in the dream was a learned old man wearing a long black coat. He was a kind of hybrid representative of the cybernetic thinking of Warren McCulloch and the spiritual wisdom of Reverend Joseph Hart. After Brad faced the glowing antlers, this man arrived to offer his navigational guidance whenever needed. In addition, he said that the future would never be the same now that a new journey had started—there was no turning back.

Soon after Brad’s vision we received an invitation to write an academic article on the topic of shamanism. Struck by the timing of it, we agreed. And so began the crazy process of hunting “shamanism” down one rabbit hole after another. That article is currently under review for publication in an academic journal. What follows is a brief summary of what we discovered about shamanism during the process.

Shamanism: An Anthropological Invention

As we dove into the academic discourse we soon found the writings of Alice, not the one related to Lewis Carroll, but the Harvard educated anthropologist named Alice Kehoe. She concluded that shamanism is largely based on fiction—the unfounded claims of religious studies scholar Mircea Eliade who never met a shaman but invented his own imaginary shaman that was inspired by the reports of early travelers to North and Central Asia. Kehoe’s actual words were not as kind as we just represented them. Suffice it to say that a trip to a well-stocked university library and some serious study show that shamanism, as it is known and understood in modern times, is suspected as being either a partial or whole fantasy of anthropology.

Any proposed universal definition, core experience, or common practice of shamanism that does not acknowledge the surrounding disagreements, diverse perspectives, and varying academic shamanic realities is evidence of shoddy scholarship. In addition, referring generally to healers or spiritual elders in indigenous cultures as “shamans” is an error that ignores the many differences found in their practices, roles, and names. The terms “shaman” and “shamanism” arguably only have meaning inside both academic discourse and in the popular imagination of modern cultures who have lost or perhaps never had “shamanic” traditions. When addressing these audiences we too use these terms despite their contested meaning.

As we plowed through old and new texts on shamanism, it became clear that the topic was laden with confusion, divergent conclusions, and fierce debate. For example, Roberte Hamayon, a leading scholar of Siberian shamanism, concluded after nearly 30 years of fieldwork: “the shamans of traditional societies would be absolutely astounded to learn of claims that they seek to alter their state of consciousness.” There is a growing opinion among scholars that shamanism may not primarily involve trance or journeying—and those who uncritically followed Eliade were led astray.

Getting chemically, sonically, or physically closer to shamans does not necessarily correct the scholar’s theoretical outlook. Many anthropologists’ published conclusions about the shamanic traditions with whom they conducted fieldwork are fraught with bias and distortion (however unintentional it may be). Sipping a shaman’s tea, learning their style of percussion, or dancing all night with them does not remove the observer’s theoretical blinders that filter and categorize the experience. The interpretive maps that academic journals publish too often obscure the experiential territory.

For instance, a broad term like “trance,” readily used by anthropologists to explain shamanic experience, is not necessarily a relevant construct to the shaman. In addition, the anthropologist may highlight the costumes, feathers, cosmological constructs, or drum more than a shaman’s prayer, song, or emotion. If you do your homework on shamanism, it becomes abundantly clear that it is one of the most confusing topics on the planet and those who spend a lifetime studying it often remain unsure what they have been examining. The anthropologist or scholar of religion ends up mostly reporting their own mapmaking and explanatory devices. Seldom is the shaman’s experience conveyed in the shaman’s own words and conceptual frameworks.

As we compared our own experiences with the way others discussed shamanism, we found that both scholars and contemporary practitioners were unclear and often sloppy with their basic terms. As Hulkrantz (1989: 44) concluded: “[There] is a chaos in the understanding of what shamanism is: most authors dealing with the subject never give any definitions . . . Those who define the subject differ widely.” Sidky (2008: 82) was specifically critical of those following the trail that began at Professor Eliade’s office in Chicago: “Writers in pursuit of the archaic shaman are chasing a phantom whose ritual enactments belong . . . to the inner recesses of Eliade’s free-flowing imagination.”

In conclusion, we found that the literature on shamanism was so riddled and muddled with inconsistent definitions and opposing assumptions that several times we threw away all that we had written in the summer, pledging to never write about shamanism or ever mention it again. Then another unexpected dream would jolt and inspire us, and we’d start the task all over.

Shamanism: A New Age Marketplace Invention

An important question arises for today’s spiritual seeker: how is it that New Age spiritual teachers claim that they know what shamanism is and how to easily do it, while not mentioning all the debates and conflicting opinions of scholars? The three main suspects who are usually lined up to account for the popular view of fantasized shamanism are also the main targets of academic criticism: Mircea Eliade, Carlos Castaneda, and Michael Harner. Eliade, a scholar of religion, exercised his intuition and imagination to such an extent that he became one of the most disputed scholars in the entire history of religious studies. But, to his credit, he actually heavily footnoted his writings and included the dissimilarities as well as the similarities among the shamanic traditions he discussed. His scholarship was more complex than either his enthusiasts or critics let on.

Castaneda also had literary skill, but it was aimed at popular book success rather than persuading a community of scholars. Insiders knew that Carlos Castaneda was a capable writer of fiction and that his accounts were cleverly made up (see Joyce Carol Oates’ 1972 letter to the New York Times). His sorcery was limited to a literary brew of words that intoxicated the minds of those readers fascinated by and wanting to practice brujeria. Simon and Schuster, the publisher, knew this and profited from the professionally staged and strategically marketed illusion. A few people close to the editor also knew it and Brad was near that inner circle. Now after the magical power tales have come and gone, let us not forget that a readership of 28 million readers were duped into believing his stories may have really happened. Popular success clearly is not a reliable indication of shamanic validity.

How did Castaneda’s fiction become considered factual? In no small part the enthusiastic endorsement of a university anthropologist helped make it a believable alternative reality. Michael Harner publicly declared that Castaneda was telling the truth and that the magical power in his tales was empirically real. This unbridled endorsement helped set the stage for Castaneda to become a bestselling author who made the cover of Time magazine. Later Castaneda returned the favor and claimed that Harner was equally real and true. Surrounding both of them were other academically trained folks who had gained spiritual popularity as heroes of the post-psychedelic era, now called researchers of entheogens, God molecules, altered states of consciousness, and shamanic realities. This social club promoted one another and the non-academic world accepted this as meaningful validation.

Eliade’s career remained inside the ivory tower at the University of Chicago, whereas Castaneda avoided the university and the public as Harner left academia to seek more popularity. The invisibility of Castaneda combined with his bestselling author status motivated people to search for him across several continents. On the heels of the mad rush to find a flying Don Juan, Harner’s promised easy entry to the invisible world of shamanism inspired New Age seekers to sign up for his workshop offerings.

While Eliade never became a New Age household name like Castaneda and Harner, he was the starting place for the popular view of shamanism as a “journey” fueled by some kind of mind-altering technique, from peyote ingestion to rhythmic entrainment. Without Eliade there would be no Harner whose work is an extension of Eliade’s dreaming. Without Castaneda, there would likely be no marketplace for shamanism. He was the bridge between literary confabulation and the “shamanic practitioner,” connecting Eliade’s imaginary shaman with Harner’s invented shamanic techniques. The journey from Eliade’s desk to Castaneda’s writing pen leads to Harner’s guided fantasy method. This is the journey to Ixtlan, the adolescent Shangri-La of neon-shamanism.

None of these three adventurers, by any stretch of the imagination, can ever be seriously considered a spiritual teacher anything like a D. T. Suzuki or a Paramahansa Yogananda, as some enthusiasts suggested. These latter two men were congruent embodiments of long-standing religious lineages. Pursuing altered consciousness that promises masses of people easy-pleasy access to magical power has nothing to do with wisdom teaching. It is the capitalist’s blend of literary imagination, Madison Avenue marketing skill, and a California-hosted placebo effect—something worthy of sociological study, but not deserving of spiritual devotion.

The Emotion of Ecstasy

Again and again we dove into a rabbit hole and chased another hare. Finally, Little Seagull Man, Brad’s Guarani Indian colleague from the lower basin Amazon, came to Brad in a dream and said: “The most important experience of a shaman is emotion. Follow the shaman’s emotion.” Afterwards we remembered that Eliade had subtitled his classic book on shamanism: “Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy,” and wrote in the beginning chapter that he felt this was the “least hazardous” definition of shamanism. However, not only did his work become widely subjected to the hazards of controversy and a favorite target for attack, few scholars bothered to further define or critically explore what was meant by “ecstasy.”

Eliade himself did not sufficiently account for his use of the words “ecstasy,” “ecstatic,” or “trance” to refer to the shamanic experiences he described. He employed these terms as if they carry a universally agreed upon meaning that neatly matches reports of shamanic experience without causing distortion—this was one of his main errors of scholarship.

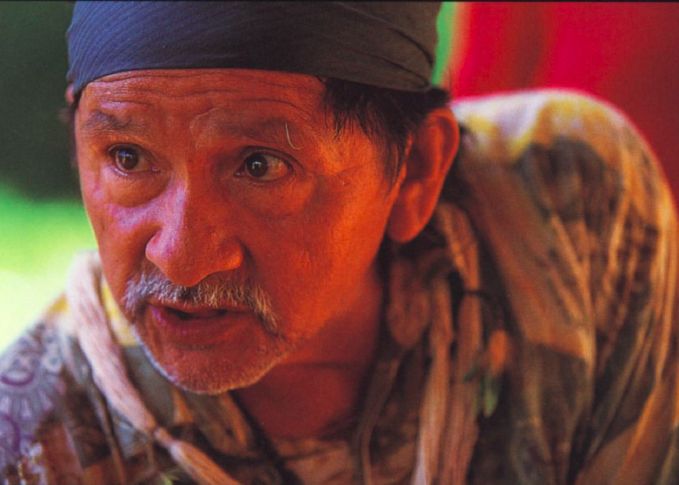

Ava Tape Miri, or Little Seagull Man. For more on his life see the book, Guarani Shamans of the Forest, edited by Bradford Keeney

Before our summer adventure with glowing antlers and theoretical sink holes, we years ago had chosen the term “Sacred Ecstatics” to describe our own work as valuing the heightened emotion of ecstasy inspired by the sacred. What we didn’t realize was that “ecstasy” meant so many different things to different scholars. Sometimes it is even defined as a somatically still, non-emotional, unconscious state—the exact opposite of heightened emotion and its subsequent enhanced sensory awareness and elevated kinetic activity.

This discrepancy in the definition of ecstasy is more than a scholarly aggravation. It has led to the gross misunderstanding and narrow definition of what constitutes shamanism, including the unexplainable gap between anthropological evidence and both scholarly and neo-shamanic conclusions about shamanic experience. This rampant confusion about ecstasy and shamanism became clearer as we further researched shamanism studies and it became the focus of our paper—reexamining the ecstasy of shamanism.

In a nutshell, what we found is that ecstasy is often not used to indicate heightened jubilant emotion and its somatic expression—the old fashioned “fire in the bones” of spiritual ecstatics. For reasons that remain unclear Eliade equated ecstasy with “cataleptic trance” (a comatose state) during which he deduced the visionary “journey” takes place. He de-emphasized the wild emotion and performance fury that preceded the cataleptic state, though he includes the reports of such behavior in his book. Eliade and many other scholars extracted and rendered most important the ending of a whole sequence—bracketing the final moment when a mystic, shaman, or healer drops to the floor and goes comatose (i.e., is “slain by the spirit”) or postures a frozen stare like that described by St. Teresa of Avila.

Ecstatic emotion and its body commotion come before the final collapse into unconsciousness, something ignored and/or forgotten by observers who look only at the final pose and the post-hoc reports of a shaman’s vision. This distortion misses the whole ecstatic ride and replaces it with an after effect whose importance is then exaggerated by the observer. Cataleptic trance does not always follow ecstatic fervor, and it is presumptuous to suggest that the experience is equally and universally valued among shamans. Strong shamans don’t always fall down, pass out, or go catatonic. The Kalahari Bushmen, for example, prefer keeping their shamans (“doctors”) awake and standing up to dance, not lying or sitting unconscious.

Harner followed Eliade but further conflated and reduced “cataleptic trance” to a “light trance” that he named a special “shamanic state of consciousness”. The body and its heightened emotion were once again minimized and the “trance shaman” continued to eclipse the numerous historical and contemporary reports of shamans singing, dancing, and expressing emotional fervor. Michael Harner thought that ecstasy was solely a trance induced by monotonous rhythm and was genuinely surprised when Brad pointed out the word’s etymology and how it primarily refers to heightened emotion, with trance as one possible outcome.

Harner and other neo-shamanism teachers were also unaware or did not mention that they had departed from Eliade’s “cataleptic trance” and instead, spoke of trance as if it were a generic experience, missing the research that demonstrates that there are many kinds of trances that change constantly; trance is less a state than a dynamic. (At the time Brad had studied trance extensively and was coauthor of the biography of the founder of clinical hypnosis, Milton H. Erickson.) The naive understanding of trance in neo-shamanism has since been critiqued by several scholars, yet remains ignored by its current practitioners.

More interestingly, most teachers of neo-shamanism Brad talked with over the years believed that extreme emotion made a situation more uncontrollable and this is why they claimed to personally avoid it. They felt it was “dangerous” and that people might have “psychotic breaks” or “nervous breakdowns”—mirroring the same Neoplatonic fear of the body and ecstatic emotion that permeates many of the world religions. In other words, they regard the emotionally ecstatic performance of shamanism in the way early historical travelers did—as comparable with a mental disorder like “Arctic hysteria.”

This prompted Brad in the past to announce that ecstasy and its “shaking medicine” may be the last taboo—people are afraid of somatically felt and expressed bliss. Accordingly, today’s neo-shaman promotes an envisioned journey that takes place primarily inside the head rather than an embodied performance that moves and interacts with others to convey intense emotion and ignite involuntary movement. As we reexamined the literature on shamanism, we found that no matter how much scholars (and neo-shamanic practitioners) disagree with one another, they are all alike in this regard—they keep shamans inside the shaman’s mind and far away from the body’s reception and expression of sacred emotion.

Ecstasy Versus Guided Imagery

When Michael Harner first contacted Brad, he was very complimentary and wrote an endorsement of Brad’s work with the Kalahari Bushmen. After he got to know Brad, Michael framed their differences as Brad being more a shaman of the African diaspora while he was more associated with what he hypothesized were the tributaries of Siberia that reached as far as the Amazon and the North American plains and elsewhere. Brad never accepted this way of framing their differences because he had read too many early travel reports and anthropological findings that described how there was a lot of shaking going on everywhere in the world.

Furthermore, though it was convenient for Michael to emphasize Brad’s experiences in Africa, he did so while aware that Brad was intimately involved with shamans in many other parts of the world. Brad had experienced ecstatic expression wherever he went, though its form took place to different degrees on the spiritual thermometer. The idea that body excitation and non-monotonous rhythm and song only take place in Africa is not supported by anthropological evidence or personal experience. It is more likely another example of the Eurocentric worldview that leaves bodily experience out of the equation in favor of what is envisioned by the mind. In general, nowhere in Brad’s experiences among shamans in North America, South America, Asia, or Africa did the shamans’ performance look, sound, or feel anything like the performance of Harner’s core method.

While Michael Harner taught a unique practice to the world, it is by no stretch of the imagination or the body a representation of what is at the core of all the traditions typically regarded as shamanic. Such a claim is far more fantastical and phantasmagorical than Eliade’s tentative and tempered generalizations. We wish Harner had better logically typed his abstractions. We value Harner’s method as a creative extension of the psychological technique called “guided imagery” or Katathym-imaginative psychotherapy (KIP) invented by Hanscari Leuner, M.D., one of the early LSD researchers Harner likely knew.

The protocol taught by Harner’s organization adds rhythm and the suggestion of magical travel that follows a cosmological structure. While Harner had former academic experience and knew the criterion for scholarly exposition and legitimization, his post-academic career developed the habit of not mentioning other studies that came to different conclusions than his own. Harner could have benefited from the use of more scholarly street smarts and culturally appropriate etiquette to frame his work as more experimental and exploratory than absolute and universal.

A Shaman’s Song

On the night we finished what we privately called the “red antler paper,” Brad dreamed of Little Seagull Man again. This time he simply sang Brad a song. We knew we had completed our assignment. The journey had brought nightmares of battling demons and even resulted in body pains. But we came through as we each were given enough sacred dreams along the way that brought medicine and guidance. The paper we wrote serves bringing back the aspects of shamanism that also have been equally ignored by many other religions over the years—the whole body, its heightened emotion, and the conveyance of such emotion by song, dance, and vibratory touch.

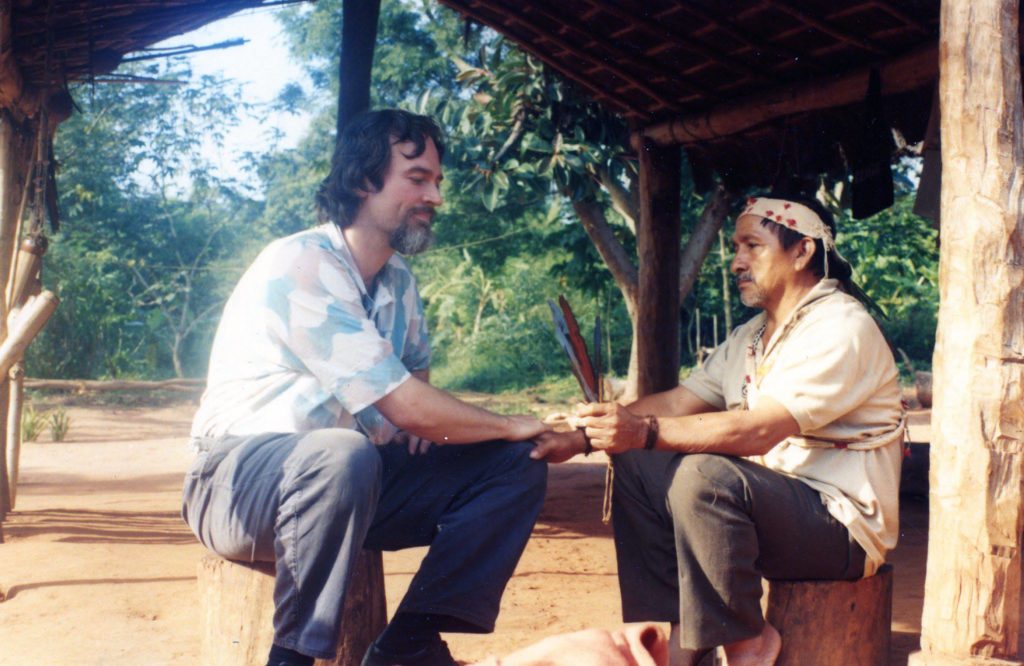

Bradford Keeney and Ava Tape Miri, or Little Seagull Man

At the end of the shamanic day and night, the shaman is not found in a visionary travel report, a molecular compound, an EEG, or a brain scan. The shamanic performance we want to bring back to the stage is ignited and driven by an emotional relationship to the sacred. Everything else that is part of this shamanic show serves elevating this emotion and its spontaneous expression. The shaman, if we care or dare to still use this noun, is not always sitting, drumming, and entranced in a daydream journey to predetermined locales.

We come to the topic of shamanism as both multidisciplinary scholars and practical teachers of ecstatic spirituality. As ecstatics we emphasize the vital importance of heightened sacred emotion and how it triggers autonomic expression of the body in shamanic experience. This kind of ecstasy has deeply touched our own lives and is valued among the shamans we have known, but it has too often been minimized or altogether ignored by scholars even when the studied shaman reports it. While we respect any purported spiritual experience and diverse ways of explanation, we oppose the way some shamanism scholars and popular authors promote their personally preferred assumptions about a trance-like journey at the cost of eclipsing the entire spectrum of shamanic experience. Such totalizing claims represent the worst of cultural, scholarly, and experiential appropriation.

As scholars our goal is not to compete for the most correct definition of certain terms or the best interpretation of “shamanism.” Instead, we call for specifying how and whether a wide sweeping theoretical generalization is linked to a detailed specification of the whole enacted performance rather than a fragment (see our qualitative research method, Recursive Frame Analysis). In addition, scholarship must at least acknowledge the existing literature and the challenges posed by other scholars. Furthermore, if words such as “ecstasy,” “trance,” or “journey” are used, the different meanings of their usage must also be addressed along with the investigator’s definitions.

In summary, reporting more of the whole context rather than reducing it to extracted elements better assures avoidance of a context-less account of shamanism, the latter being intellectually meaningless and spiritually pointless. If an author claims to represent shamanism to others, then he has a responsibility to account for how his observations are filtered, his interpretations construed, and account for why others experience the same subject differently. Otherwise, history may repeat an error that has been uncritically accepted as a fact, leaving no empirical clue about the experience named.

Beware the Temptation to Fake a Body Shake

Finally, we warn that our own students and colleagues must carefully guard against committing a similar error of spiritual reductionism that has led students of neo-shamanism astray. Just as shamanic practitioners believe that they are making contact with a spirit world just by imagining it while listening to a drum beat, sometimes our students of Sacred Ecstatics think they are having the same experience as a Bushman doctor or trembling healer simply by shaking and shouting like one.

Believing that shaking alone is a magic bullet will as easily lead to the wisdom null set. Anyone can be taught to act like a trembling, bouncing, quaking shaman. Trigger an involuntary twitch and the body will really get going. However, this action no more guarantees admission to the big mystery room than does entrainment to a monotonous rhythm or excitedly waving a toy magical wand. Furthermore, more intense trembling and shaking do not add up to more n/om, seiki, life force, or embodied spiritual energy.

It is the emotion of sacred ecstasy—not the shaking body—that matters most. When such emotion circulates within, the body may spontaneously jolt, tremble, shake, and leap with surprise and joy. All the latter commotion, however, is a secondary and not a primary experience. When more sacred ecstatic emotion arrives, sound and song become more important than physical movement. At the utmost height of sacred emotion is often found the least wild body action—trembling accompanies a melodic line while riding a changing rhythm, all aligned to celebrate the felt closeness to the source and force of life.

Aim to feel close to the divine and then all else follows. Enter into the whole of holiness to get spiritually cooked. Even your ideas and practices concerning shamanism, healing, spirituality, religion, and everyday life itself will be subjected to the changing nature of divinity. Above all other experience is the emotional impact of sacred ecstasy—feeling close to the Creator. This pulls you into the big room where you no longer care whether a shaman exists or not, and you forget pursuing magical power, achieving a shamanic journey, attaining mindfulness, experiencing body-full-ness, satori, enlightenment, or any kind of altered state. You are completely satisfied to be spiritually cooked by an atmosphere that dips you in infinite divine love.

If you’d like a draft copy of our academic paper, please email us at keeney@sacredecstatics.com. Be forewarned that it’s written for a scholarly journal so it is more formal than we usually write in the context of Sacred Ecstatics. But if you are going to use the word “shaman” or “shamanism” in your discourse, you might benefit from better understanding that there is a lot of uncertainty, questioning, and challenging going on about the use of these names. Hopefully, you will be more careful, precise, and humble when speaking about this topic again—we certainly will.

In addition, be careful when thinking about shamanism because you too might dream of facing someone with glowing red antlers who reminds you that the Arctic shamans knew how to light a fire and melt a frozen posture. Such a moment will set your soul ablaze. Then you will discover that souls were never lost. They only went ice cold and were in need of a thaw in the presence of a big awe. The modern world (both East and West) still waits to be introduced to shamanism whose emotion and commotion can spiritually cook, setting antlers, hearts, and bodies on fire.

– The Keeneys, November 2018

Subscribe to our newsletter, Fire in the Bones. Our next Guild season starts in the fall!

Two of the sources earlier referenced. Complete references for books or authors mentioned are included in the academic article.

Hulkrantz, Ake (1989). “The Place of Shamanism in the History of Religion,” In Shamanism: Past and Present. Hoppál, Mihály, and Otto von Sadovszky (eds.). Budapest: Ethnographic Institute, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, pp. 43-52.

Sidky, Homayun (2010), ‘On the Antiquity of Shamanism and its Role Human Religiosity,’ Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 22: pp. 68-92.