When to Add Some Chitlins

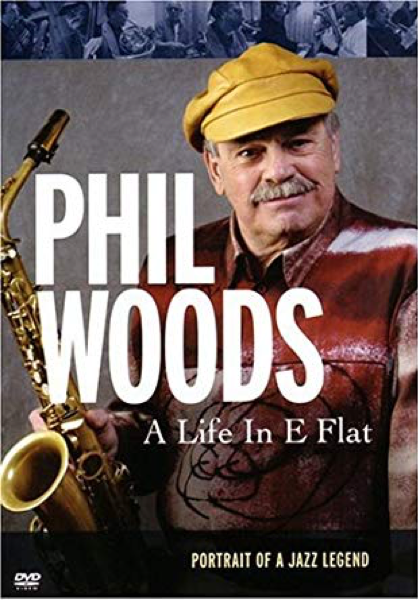

A Spiritual Classroom Visit with Jazz Saxophonist, Phil Woods

I have several times gone to a visionary classroom that is located in a skyscraper hotel in New York City. There I once met a woman shaman with glowing red antlers. I also formerly met jazz saxophonist Richie Cole in this same place and was given a music lesson. Last week, I again went to this NYC hotel where I encountered saxophone player, Phil Woods (1931-2015), espousing deep fried soulful wisdom.

Upon waking from the dream, I remembered the story that Woods, nicknamed the “New Bird,” told about meeting Charlie “Bird” Parker. A young Woods had recently graduated from Juilliard and also had memorized popular songbooks, yet felt totally stuck in a menial job performing for a burlesque show. He felt his career was going nowhere and blamed everything from his instrument to his reed and even his strap. Then he heard that Charlie Parker was playing across the street. On a break, he went to check him out and found Parker didn’t have the right kind of sax—he was playing a borrowed baritone rather than an alto. Parker asked Woods if he could use his alto sax.

Listening to Parker play, Woods was astonished to hear his instrument and reed sound perfect on a rendition of “Long Ago and Far Away.” After a few songs Parker turned to Woods and said, “Now you play.” Recognizing this rare (though daunting) opportunity, Woods played a song. After, Parker said these four simple words that would change Woods’ life: “Sounds real good, Phil.” That was the turning point of his career. Immediately, Woods got to work and recommitted himself to becoming an artist, and the rest is history. Phil Woods, who always played with fire, became one of the greatest recorded alto sax players of our time.

Even if you don’t listen to jazz, you have likely heard Woods play sax on Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are,” Steely Dan’s tune, “Doctor Wu,” or on the Paul Simon album, “Still Crazy After All These Years.” He won four Grammys including one for an album with an orchestra conducted by Michel Legrand, on which he recorded one of the best renditions of “The Windmills of Your Mind.” (Michel Legrand composed the music for “Windmills,” the song Hillary dreamed in the Beethoven vision. See our book, Climbing the Rope to God, for the story. Michel Legrand passed away last week).

Putting Some Grease on It

In my dream, Phil Woods was giving a master class on the art of embellishing music, a teaching that can be equally applied to living life as jazz. Wearing his traditional captain’s hat (he was definitely my spiritual captain in the vision), Woods swore like a sailor: “Put some grease on that motherfucker,” he said, referring to the need for loosening a musical line. In another moment, he said, “You need to know when to play it straight and when to add some ‘chitlins’ in the piece.”

Woods could be wild or tame, raw or well done, tough or tender—he knew what to add or subtract at the right moment with the right amount. I woke up from the dream trembling with excitement, unable to remember all he had taught. More than anything else, I had learned that the art of jazz teaches the art of ecstatic living. I felt plugged into jazz electricity whose deep African musical roots were grown, fed, and greased by what would later be called “the chitlin circuit.”

I later discovered that in 2007, Phil Woods, dying of emphysema, actually carried his oxygen tank to the Sheraton Hotel in New York City to take the stage one more time at the annual conference of International Jazz Educators. There he had no apologies for the way he lived his live with all its ups and downs. In an article celebrating his life in Downbeat Magazine, I found some of what I had heard in my dream in that NYC hotel located in (eternal) Times Square. Near the end of his life Woods said, “I just play songs, man. I play bebop. I’m influenced by Harold Arlen and Charlie Parker and Jerome Kern and Thelonious Monk. I don’t consider myself in those ranks creatively, though. I keep the flame going. I’m very happy to be a good player. A pro. I’ve sometimes referred to myself as ‘a soldier for jazz.’” Phil Woods left us with this advice: “Music is the journey. You never arrive in music; the work is never over.”

When he began his musical journey, he thought he had what it took to succeed. Woods went to New York City to study under the great jazz pianist, Lennie Tristano. Decades later, when asked what he learned from Lennie, he said: “I learned that I didn’t know anything and that I had a lot of work to do.” This is also the first important lesson in the art of ecstatic living—feeling the need to learn and surrendering to the fact that there is much you don’t know. Later when Woods became an elder master of jazz, students were often terrified to play for him, telling him they were too awestruck. Woods would tell them, “Hell, get over it. I had to play for God [Charlie Parker].”

Jazz bassist, composer, and arranger Chuck Israels said this about the master sax man’s life: “When Phil Woods stood up from the lead alto chair to play his solo feature, the atmosphere changed. Phil played as if there were no tomorrow.” Phil Woods taught us that mastery requires exceptionally hard work, unfiltered truth, and the courage to head to the cutting edge. The ecstatic life embodies the wisdom of Phil Woods’ advice to budding jazz musicians: “…it should be more aggravating, it should stick in the craw. If it’s too acceptable, it’s lacking color and it’s lacking a bit of humor.”

Praise the Lard

In order to get spiritually cooked you need to be altered, seasoned, and further embellished by life. Don’t get too smooth, and don’t ignore the refrigeration that extinguishes the heat. Learn from it—study how it puts out the fire. As Phil Woods taught, “Listen to the music you don’t even like and see why you don’t like it.” If you can’t discern what’s cold, you won’t be able to feel what’s hot.

If you only like music–or spirituality–that is too smooth and cool, listen again to the alto sax man who lived his life in E-flat: “Whoever invented smooth jazz, man, I wanna kill ’em: You’re turning an art form into a hooker.” A love supreme, the stuff of dream, is found in the beauty and roughness of jazz and life rather than in the fat free Muzak whose dull tones were designed for drones.

Never forget that soul and chitlins are inseparable. The intestines of a pig, boiled down, fried up, and served with apple cider vinegar and hot sauce is a metaphor like the mud of Muddy Waters. Both the grease and the mud are needed to ease, slip, and slide the grip so the music can be released into all the parts of life that have lost their soul. You gotta know when to sling the mud and when to add some grease and chitlins rather than obsess over thinking, eating, and playing clean.

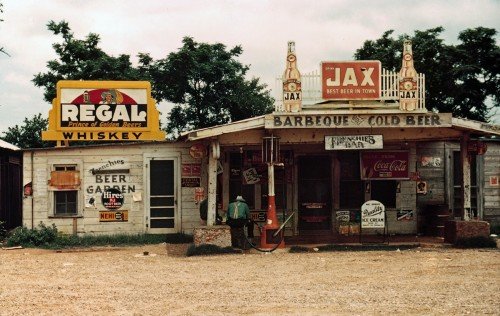

You have to learn how to “Praise the Lard,” the name of a soul food spot Hillary and I once found in the back roads of Mississippi. As one elderly black church mother once told me, you have to “get dirty for the Lord” in order to be clean as a musical whistle in cosmic soul time. Phil Woods boasted that he ate no organic food, preferring soul food, knowing that it’s not about what you eat, but how you meet and greet the culinary, musical, and mystical heat. Get down in order to climb the ladder that takes you all the way up to a tuneful, hornful, and soulful heaven.

Have a boiled, grilled, barbecued, and deep-fried serving of the “Body and Soul” of Phil Woods:

-Brad Keeney, with Hillary Keeney, January 28, 2019